Truth & Reconciliation Part 1: Can all Kashmiri Muslims be blamed for Pandit exodus? (Sualeh Keen, 2020)

|

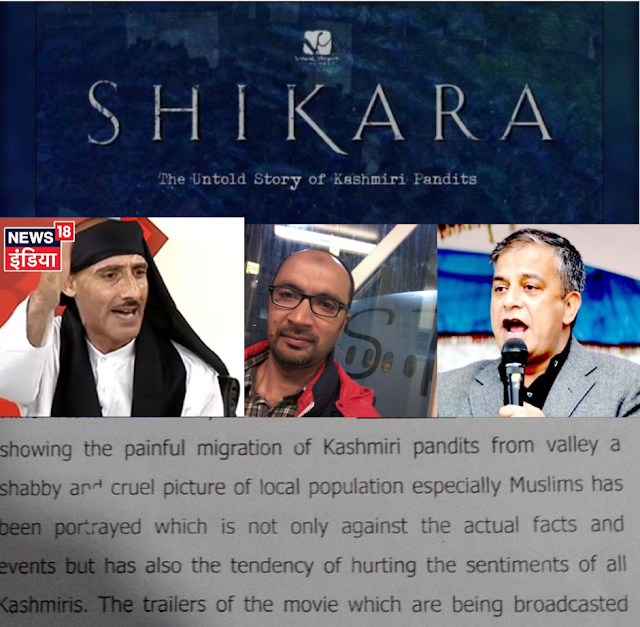

| Yasin Malik, whose terrorist organisation JKLF, initiated the drive against minorities and other victims in late 80's. |

Truth & Reconciliation Part 1: Can all Kashmiri Muslims be blamed for Pandit exodus?

Obviously, the conflict has extracted a bigger cost from the Muslim majority. We need to understand that in terms of murders, kidnappings, rapes, loot, and humiliation at the hands of terrorists, the Muslim Kashmiris who did not flee from the valley have suffered the most, because they had to endure terrorism for three decades and still do. Muslims also paid the price for counterinsurgency operations, excess use of force in mob control, fake encounters, torture, harassment, and humiliation from the counter-terror apparatus.

With so much of suffering all around, why is it that Pandits and Muslims don’t share a common sense of loss (generally speaking)? Why is there an undeniable apathy, if not antipathy, between the two communities, though it is far more pronounced in the online public world, and not so much in private, peer-to-peer world?

In this article, I highlight the factors that have led to a (seemingly) unbridgeable chasm between the two communities and try to foster a mutual understanding between the two, through cold logic rather than through emotional appeals.

This state of 'irreconcilability' sets the stage for reconciliation, which I will deal with in Part 2.

Read on.

“Pandits didn’t start the fire, Muslims did!”

A common refrain from my Pandit friends is:

“Indeed, the past three decades have been tragic for Kashmiris from both communities. However, for my tragedy, i.e. the tragedy of Pandits, my Muslim brother was—directly or indirectly— responsible, while as, I was in no way responsible for his tragedy...”

It’s a fact that Pandits, as a community, are pure victims, i.e. they did not pick up a fight with Muslims for which it could be said that they deserved to be ethnically cleansed from Kashmir.

On the other hand, the case of Muslims is mixed: some were perpetrators, some were pure victims, and some were perpetrators who also suffered. And this Pakistan-sponsored terrorism and Tehreek-e-Azadi was always a Kashmiri Muslim project; not for non-Muslims like the Pandits and Sikhs of the valley (or even of the Muslims of Jammu and Ladakh). The Tehreek is dubbed the “unfinished business of Partition” and we know only the Muslims wanted Partition in 1947.

The Kashmiri Muslims, who directly targeted, killed, looted, raped, and threatened the Pandits are obviously responsible for the exodus and miseries of Pandits primarily. Indirectly too, all the Muslims (neighbours, students, acquaintances, etc. of Pandits), who participated or supported the armed uprising and raised anti-Kafir and anti-Pandit slogans, were responsible for creating an atmosphere that the Pandits and other non-Muslim minorities found terrifying.

So then, are all these Kashmiri Muslims to be held guilty for becoming a part of the Jihad Zeitgeist of the early 1990’s and being directly or indirectly involved in the expulsion of the entire Pandit community from the valley?

Yes, guilty as charged.

So why then should Pandits feel any compassion for the Muslims after their terrorism was brutally crushed by the Indian State, resulting in the death of terrorists, their supporters, and innocent Muslims caught in the crossfire? As the Kashmiri proverb goes, Anim swoy, vowum swoy, lajim swoy paanasee (I brought the stinging nettle, I sowed the nettle, I only was sting by the nettle). What goes around, comes around. What you sow, so shall you reap. Karma is a bitch, no?

Well, no, not exactly.

All Muslims were not, so to say, “asking for it”. The Muslims who neither became terrorists nor supported Jihad, also suffered from the hands of the same terrorists, who only shared their religion with them but not ideology or actions.

Although the Pakistan-sponsored uprising was popular in 1990, not all Muslims supported the violent movement, especially not those who had something to lose from this revolution, this coup d’état and change of guards, for example, the mainstream politicians, government officials, and other beneficiaries of status quo.

Private estimates of the popularity of Jihad vary, depending on whom you ask. In hindsight, I reckon the support for “Kashmir banega Pakistan” wasn’t more than 30% of Kashmiri Muslim men, and those who supported the Jihad mostly comprised of uneducated / educated unemployed / underemployed youth. This anti-India proxy war launched by Pakistan in Kashmir was a masculine enterprise, as all wars are, appealing to the ‘ghairat’ of the Mard-e-Moomin, with macho Rambo-style gun totting Mujahiddeen as ‘heroes’ and poster boys. Generally speaking, Muslim women did not participate in the mobilisation or were kept away from it (with exceptions, of course). Therefore, the actual support base for terrorism among Muslim adults would be lower when both genders are considered. However, for the sake of argument, let’s assume that in 1990, half the Muslim adults (men and women) or 50% were supportive of terrorism. That still leaves out half of the Muslims in 1990, who were not—neither directly, nor indirectly—responsible for the Pandit exodus.

Indeed, it wasn't only the members of the Pandit minority that were targeted, but many Muslims as well, and in fact, more than any minority. Most Muslims today still curse that phase and say, "Fakh tul amyi militancy! Tabaah karikh!” (“Militancy has spoiled Kashmir! Ruined us!”), though it is something that they could only confide in private, so far.

Then there is the generation of Kashmiri Muslims—boys and girls—who were too young or yet to be born in 1990. This youth demographic bulge forms the bulk of Kashmiri population today.

As per the J&K census figures from 2011 (assuming a similar distribution in Kashmir division in present times), nearly 62% of Kashmiri population is under 30 (00-29) years of age today. That means, more than half the Kashmiri population was not even born in 1990. And if we include those Kashmiris who were born before 1990, but were minors under 10 years old (00-39), we get a whopping figure of 76% population of Kashmiri Muslims was not born or was too young in 1990 and therefore have no direct or indirect culpability for the Pandit exodus.

J&K Population in Various Age Groups (2011)

| |||

Age Group

|

Persons

|

Share (%)

| |

00-04

|

14,14,884

|

11.28

| |

05-09

|

14,11,973

|

11.26

| |

10-14

|

14,13,853

|

11.27

| |

15-19

|

12,37,462

|

9.87

| |

20-24

|

11,60,913

|

9.26

|

Share (00-29):

61.60% |

25-29

|

10,86,122

|

8.66

| |

30-34

|

9,26,903

|

7.39

|

Share (00-39):

75.67% |

35-39

|

8,37,945

|

6.68

| |

40-44

|

7,14,085

|

5.69

| |

45-49

|

5,90,790

|

4.71

| |

50-54

|

4,68,566

|

3.74

| |

55-59

|

3,40,031

|

2.71

| |

60-64

|

3,22,726

|

2.57

| |

65-69

|

2,03,965

|

1.63

| |

70-74

|

1,84,019

|

1.47

| |

75-79

|

85,076

|

0.68

| |

80+

|

1,26,870

|

1.01

| |

Age not stated

|

15,119

|

0.12

| |

Total

|

1,25,41,302

| ||

And of the remaining 24% who were adults in 1990, we have assumed only 50% were directly or indirectly responsible. That means that Pandits effectively have genuine grievances with only 12% of Kashmiri Muslims of today.

And if we factor in the fact that most terrorists were subsequently killed in encounters, it leaves an even smaller percentage share of the Muslim population alive today that can be deemed blameworthy: the Muslim perpetrators—whether terrorists or their supporters—the ones who actually committed or participated in crimes, some of whom are still around, walking free, some unpunished.

Nevertheless, as explained above, these perpetrators of crimes against humanity in early 1990's are a small but powerful fraction of the total Muslim population today. Considering the much larger number of Muslims—male and female, young and old—who are not the villains of Pandit exodus, it would be unfair for the Pandits to hold a grudge against all Kashmiri Muslims and expect remorse or apology from them collectively (though, as human beings, one can expect sympathy).

Of course, a Pandit victim has every right to blame the individual "brother" who did inflict harm on the victim, and if the perpetrator is still around, let us file a case against him and take him to the court. However, let us not ascribe "responsibility" for the Pandit exodus to the entire Muslim community. The state is also guilty of omissions and commissions, but we blame individuals in the system, not the State, per se. In the pursuit of justice, we need to be specific, not generalized.

“Damned if you do, damned if you don’t!”

Another complaint of my Pandit friends is:

“What the terrorists did, that was expected of them. But we were shocked at the silence of people, who were neighbours. They did not take a stand against the harassment of the minority community.”

On the surface, this is a fair complaint, but what’s problematic is talking in plurals: Neighbours, they, community. That some Muslims killed, raped, looted Pandit property and shouted anti-Pandit slogans is a fact, but please don't generalise. It serves the objectives of only hate-mongers, radicals, and fascists to cast an entire community as purely evil. We have to understand the different psycho-dynamics of different people: the good neighbour, the evil neighbour, the good colleague, the evil colleague. Don't throw the baby out with the bathwater.

Basically, some of my Pandit friends are questioning the silence of their Muslim neighbours in 1990, when even mourning for the people in the hit list was banned, at a time when some person's dead body left in a gutter by the terrorists was not approached by anybody in the neighbourhood, without even knowing if the corpse was that of a Muslim or of a Pandit. Given the atmosphere of terror, in my opinion, being vocal against the terrorists is too much to expect.

Let me give an example:

When advocate Prem Nath Bhat was shot dead by terrorists outside him home in Khah Bazar, Anantnag on 27 December 1989, separatists danced in that street on his spilt blood. And to amplify the message that no one was allowed to mourn or feel sympathy for the ones killed by terrorists, a hand grenade was lobbed into the Bhat’s home subsequently, while his family and friends were still in mourning. This triggered the immediate exodus of the extended family and friends of the deceased in early January 1990... Now, everybody knows about the terrifying murder of Advocate Prem Nath Bhat; what they probably don’t know is the chilling effect it had on Muslims, including Muslims in friendly terms with Pandits. The head of a Muslim family (also lived in Anantnag town), who worked with PN Bhat in the court, was so terrified by the shocking murder of his mentor, he ordered that a common door connecting his home with his Pandit neighbours be nailed shut. His justification of this drastic unilateral step: “We don’t want any murderer entering into our Pandit neighbour’s home from our side. We don’t want that sin upon us.” However, the Pandit neighbours viewed this nailing shut of the common door as the final nail in the coffin of lehaaz (mutual respect) for the Pandit community, the permanent closure of a centuries old door of a mutually shared history and ancestry. The pounding of the nails on the wooden door felt like lacerations in their hearts. Disappointed with their Muslim neighbours’ barring of doors, the Pandit neighbours saw no hope from neighbours and friends, nor expected any mercy from strangers. Expectedly, the Pandit family too fled from their home to Jammu and they haven’t really forgiven their Muslim neighbour for closing that door. Of course, the Muslim neighbour could have displayed some spine, but one can’t really blame ordinary people to take on terrorists who just murdered their mentor (PN Bhat) outside his home in broad daylight. The conflict, in which mere survival became the primary concern, everybody became selfish and cowardly and tried to cover their own back.

If Pakistan had done some meticulous planning to scare away Pandits, the Kashmiri Muslim majority wasn’t in the know of that plan. The Hit Lists pasted on Masjid doors in some areas included Muslim names as well, though the Pandit names at around 50% were disproportionately more than their population share. Thus, the Muslims ‘knew’ of the 'plan' in the same way as the Pandits ‘knew’ it.

Of course, not all Muslims were silent, in personal space. Ironically, the Muslim friends, who hinted or advised their Pandit friends that their homes were no longer safe, are also terms "traitors", when, in fact, the Pandit friends ought to be grateful for that advice, for they might be owing their life to that advice. It is a situation called: damned if you do, damned if you don't.

A Pandit friend told me that he owes his life to a Muslim neighbour, who, after seeing the Pandit's name on the Hit List pasted on the door of a local mosque, went straight to the Pandit's home and angrily shouted, "Haya mukhbira! Dafaa gasu yeti!” (“You police informer! Get lost from here!”), and left in a huff. My Pandit friend at that time was shocked by his neighbour's sudden hostile behaviour, but decided to flee to Jammu. Months later, after reassessing the threat to his life, he returned to his home in the valley. And when he reviewed what had happened, he went and thanked his neighbour who had ‘threatened’ him. My Pandit friend had rationalised that in an atmosphere when nobody could show any sympathy or even mourn for the people in the Hit List, the neighbour actually had pretended to be on the side of the tehreek, while ensuring that he appropriately warned his Pandit brother so that the latter did not fall to the bullets of the terrorists.

How can such a seemingly 'hostile' neighbour who was also the 'saviour' fit into any grand narrative of Kashmiri Muslims having being uniformly antipathic or indifferent to Pandits?

Of course, the two examples cited do not cover all shades of inter-community experience during those trying times, but it is hoped that such examples break the stereotypical grand narrative about Kashmiri Muslims. More than personal narratives, it’s the grand narrative that is the problem, for it miserably fails to take into account all shades of experience.

In Truth & Reconciliation, personal truth is paramount, not the grand narrative, which only serves a political agenda, least bothering about individuals.

“Your collective denial leads to my collective accusation!”

My Pandit friends say:

“I still hold the majority guilty of denying the Pandits their truth. I never held the majority guilty of crimes or of directly driving Pandits away. There is a vast difference.”

That not all Kashmiri Muslims are bad and that the entire new generation of Muslims is blameless for the exodus are things that most Pandits already agree with. Yet, we see many of the same Pandits also holding a grudge against the entire Muslim community. How does it all add up?

Simply answered, the collective denial of Kashmiri Muslims that “We Muslims were not responsible for your exodus”, leads to a reciprocal collective accusation that “No, you all are hiding your shame by denying the truth”. In other words, as long as Kashmiri Muslims deny the fact that many separatists and terrorists hounded out Pandits in 1990, Pandits (or anybody for that matter) would tend to see the Muslims as defending terrorists and whitewashing the Pandit exodus, thereby lumping all Kashmiri Muslims into the same category as the actual perpetrators.

Now, Muslims cannot do anything more counterproductive than defend terrorists, especially when many of the surviving JKLF terrorists have already accepted on record that they committed a “mistake” by targeting Pandits and driving them away. It would be far better and wiser for Muslims to also blame the terrorists for the exodus, thereby giving themselves an exit route from collective responsibility.

Sadly, most of the Kashmiri Muslims still mouth the propaganda that the terrorists normalised for three decades, without realising that it only benefits the terrorists, not the peace-loving Kashmiri Muslim who does not wish harm upon Kashmiri Pandits. Therefore, I have no hesitation in saying that Kashmiri Muslims are themselves responsible for painting themselves into the corner, with terrorists for company.

Once again, it needs to be emphasized that one cannot really blame Kashmir Muslims who were not born in 1990 or were too young to understand the events that unfolded back then. Their 'knowledge' is second-hand and they are not to be blamed; the older generation is responsible for the misinformation that the new generation has been fed.

It also needs to be emphasized that not everybody, even among the adults in 1990, was aware of what happened, due to a number of reasons:

1) Some were too preoccupied by the volatile situation to take notice what happened to the minorities.

2) Some lived in a locality where there was little contact with the minorities.

3) Due to curfew, some couldn't even know what was happening next door.

4) Some forgot what exactly happened during the build-up to the exodus, because new incidents were happening every day in 1990: massacres, killings, blasts, crackdowns, protests, encounters, targeted assassinations. Each day's news obliterated the previous day's news, until the exodus became a footnote in the Muslims’ own experience with the conflict. This is also why many Muslims genuinely don’t recall the night of 19th January, for it was a night one among many similar ones that were to follow.

5) There are also many instances where a panicked Pandit family did not even inform their closest relatives that they intend to flee during the night. This secrecy was maintained because there were incidents where militants looted the packed belongings of Pandits who were about to leave.

This vacuum of knowledge to answer the questions “Why did my Pandit neighbour leave?” or “Why the Pandits left?” was soon filled by conspiracy theories conveniently supplied by separatists and terrorists, who had orchestrated the entire expulsion drive, as they saw no role of Pandits in their violent pro-Pakistan political project.

Thus, one cannot blame the Muslims who had no role in the exodus or those who used to mouth the Jagmohan conspiracy theory because they don't know better. Besides, there were no Pandits left in the valley to ask the truth from. This cannot be called Denial; the word for it is Ignorance.

This lack of interaction with the 'other' in a homogenous all-Muslim atmosphere, this denial of truth and lack of sympathy has given rise to perceptible bad blood and mistrust between the two communities.

The Muslims need to understand that the hurt feelings of Pandits did not stem from “what happened one night in January 1990" or the occurrences in Kashmir. The hurt has more to do with what happened over the last few years of social media. The hurt has to do with almost complete lack of acknowledgement. The hurt has to do with collective angst due to persistent denial, which has increased over years.

Under such circumstances, a Young Kashmiri Turk shouldn’t be surprised if he (erroneously) gets called a terrorist or terrorist sympathiser if he denies Pandits were driven out by a violent Islamofascist movement in Kashmir in 1990.

Pandits also need to realise that not every denier was a perpetrator, and be extremely patient with the Young Turks, most of whom are ignorant and brainwashed.

Ok, all Muslims not bad, but where are “Good Guys”?

My Pandit friends say:

“The so-called good guys were silent then; they are silent now. What makes them the ‘Good Guys’?”

Three decades of vocal vehement denials by ignorant or bad Muslims, concurrent with the complete silence of their contemporaneous good guys (assumed to exist, but unheard of), leads to a one-sided picture: there are no good Kashmiri Muslims.

In Kashmir, there is a dichotomy between what one says in private and what one says in public. Why is a Kashmiri Muslim scared to speak his mind in public on a 'certain subject'? Acknowledgements for the reasons of Pandit exodus have been aplenty, but person to person, in private conversations. Ever wondered why people do not declare the same in public, shouting the truth from rooftops? With the sources and symbols of terror still around in the valley (the only killing of civilians was by terrorists in the post 5 August 2019 period), there is still a conflict of interest, a huge risk perception in stating a truth that implicates the terrorists and their cohorts. Not as an alibi, but as a well-considered explanation, I've always attributed the silence of the majority to their fear.

Kashmiri Muslims are not scared of security forces, apparently, which seems to belie a claim that Kashmiris are afraid of anyone. However, there is no single monolith called Kashmiri Muslims. It does not take much insight to realise that the 'brave people' fighting the security forces also scare their own people with their ruthlessness and recklessness; even a group of half a brat pack could make a market shut down in Kashmir until recently. Then it is easy to see that there are actually two Kashmiri Muslim peoples, not one: the Wannabe Shaheeds and the Sharafat Alis, the scared silenced ones. Ever wondered why killings by terrorists are never protested in public?

Yes, let us call the good ones Silenced, not Silent.

Indeed, the same sources of terror are still holding sway in the valley. Until 5 August, a "diarchy" of Kashmiri soft-separatists & separatists ruled in the valley. There has been a de facto rule of the same people who were the perpetrators of 1990. Due to persistent and now habitual fear, people are not in a position to stick their necks out and ask for cinema halls or a normal life for themselves, nor demand that the future of their school going children not be held ransom to the elusive Aazadi pipedream. Is it reasonable to expect Muslims to be suicidal for the sake of Pandits, who most obviously were rendered homeless but are now standing outside the fire?

If speaking for Pandits is the litmus test of one's goodness, I’m afraid it a very tough test to pass. If a Muslim like me was able to break the silence, it was only because we’re also standing safely outside the fire, like Pandits. And be vocal against the separatists, like Pandits. I self-depreciatingly call the 'fearlessness' of us, that is, few fellow Muslims in exile, “The bravery of being out of range”. And don't for a moment think that we haven’t been advised or warned a hundred times by our friends and enemies that we’re on a suicidal mission.

Don't know about you but I’d consider someone a 'good guy' even if he hadn’t been able to conquer his fears; perhaps then too he would have been a 'better guy', to those who matter most to him, because he wouldn’t have assumed a public role, which causes so much anxiety to his family overly concerned about their safety and his, most of all. [For the record, the latest threat to me and my family came in February 2020; some “bad” Kashmiris had read my last blog post via VPN.]

Besides, what do those internally displaced Kashmiri Muslims, whose homes were razed during the conflict by the security forces or the terrorists, owe to the internally displaced Pandits? What do Muslim victims of terrorism themselves owe to the Pandits, victims of terrorism also? A silent sympathy, perhaps, for a loud shout is still not advisable. Kashmiri Muslims still live in habitual fear of terrorists.

But let me bring you up-to-date:

The majority of people in Kashmir that have been muzzled so far will be the restorative medicine of ailing Kashmir. I agree that “Good Guys” not speaking against evil are no good. Cowardliness is understandable, but certainly not an admirable trait. The silent good person is a hapless person. The innate goodness will become express goodness only when it overcomes this fear. After 5 August, 2019, I see the clouds of fear dissipating in the winds of change...

(For further psychological observations on the Silence of the Majority, please go through other posts in Khamosh Kashmiri blog.)

Comments

Post a Comment